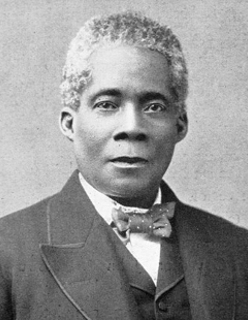

Edward Wilmot Blyden

Birthdate: August 3, 1832

Birthplace: Saint Thomas, Danish West Indies (Present-day U.S. Virgin Islands)

Date of Death: February 7, 1912

Occupation: Author, Educator, and Statesman

Profile: Regarded as the Father of pan-Africanism.

Website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Wilmot_Blyden

Number of Quotes: 21

A race is a branch of the human family with a character, a temperament, a psychology of its own,

and the characteristics of the family must be sought for in the branch as well as in the root.

This quote encapsulates his core philosophy of racial distinctiveness and the value of each race's unique

contribution to humanity, as outlined in works like The African Problem and the Method of Its Solution.

Africa may yet prove to be the spiritual conservatory of the world ... When the civilised nations in consequence of their

wonderful material development, shall have had their spiritual susceptibilities blunted through the agency of a captivating

and absorbing materialism, it may be that they have to resort to Africa to recover some of the simple elements of faith.

Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race (1887). Blyden reflecting

on how Western materialism might lead civilised nations to look to Africa for spiritual renewal.

Can you not, in your own land, work for the salvation of your own race? Can you not, in the face of all odds, build up a Negro

Nationality, a Negro Kingdom, which, by its efforts in the cause of civilization, would compel the respect and recognition of all men?

From his influential 1881 address, The Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America.

This was a direct appeal for African Americans to return to Africa and contribute to nation-building.

Christianity is for the Caucasian... a developed and established Christianity is the natural

and appropriate religion of the Caucasian... But the religion for the African is Islam.

A highly controversial but significant view. After extensive travel in West

Africa, Blyden came to believe that Islam was less

tainted by racial prejudice and more adaptable to African social structures than the Christianity preached by European colonizers.

I am aware that some, against all experience, are hoping for the day when they will enjoy equal social and political rights in this land. We do

not blame them for so believing and trusting. But we would remind them that there is a faith against reason, against experience, which consists in

believing or pretending to believe very important propositions upon very slender proofs, and in maintaining opinions without any proper grounds.

The Call of Providence to the Descendants of Africa in America (1862). Blyden's

sermon/lecture to African Americans, warning that some hopes for full equality in America were premature in the view of then current social realities.

I would rather be a member of this [Afrikan] race than a Greek in the time of Alexander, a Roman in

the Augustan period, or Anglo-Saxon in the nineteenth century.

Expressing deep pride in African heritage and identity, comparing the African race favorably even

to the famed civilizations of Greece, Rome, or the dominance of Anglo-Saxons in the 19th century.

If you are not yourself, if you surrender your personality, you have nothing left to give the world. You have no pleasure, no

use, nothing which will attract and charm me, for by the suppression of your individuality, you lose your distinctive character.

A statement affirming the importance of individual identity and personality, often cited in discussions about

the African personality

in Blyden's work.

It is a mistake to speak of the African as a degraded savage. He is simply a different

type of man, who has not yet had his chance in the fierce struggle for existence.

A direct rebuttal to the racist pseudoscience of his day. Blyden

consistently worked to redefine the image of Africa and Africans from one of barbarism to one of unfulfilled potential.

Let us do our duty in our own corner of the vineyard.

A call to action for people of African descent to focus their energies on developing their own

communities and homeland (Africa) rather than seeking validation or primary success within Western societies.

Liberia is not an experiment. It is the one spot on the West Coast of Africa where the retrograde movement of the tribes has been checked.

Blyden was a staunch, though sometimes

critical, defender of the Republic of Liberia. He argued for its legitimacy and civilizing mission in the face of external skepticism.

Mohammed not only loved the Negro, but regarded Africa with peculiar interest and affection. He never spoke of any curse hanging over the country of people. When

in the early years of his reform, his followers were persecuted and could get no protection in Arabia, he advised them to seek an asylum in Africa. Yonder

, he

said, pointing towards this country, yonder lieth a country wherein no man is wronged —a land of righteousness. Depart thither; and remain until it pleaseth the

Lord to open your way before you

. This recalls to

us Homer's blameless Ethiopians

, and the words

of the Angel to Joseph: Arise and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I bring thee word again.

Christianity, Islam, and the Negro Race (1887). Discussing the positive relationship Islam had

historically to Africa and Africans, and its regard for Africa as a place of refuge and righteousness.

Only a few, very few, civilised

people regarded Africa as a land inhabited by human beings, children of the same common Father, travellers to the same

judgement-seat of Christ, and heirs of the same awesome immortality.

Blyden making a pointed critique of how many civilised

nations

treated Africa and Africans—not as full human beings worthy of moral, spiritual, or political equality, but often merely as objects of commerce, exploitation,

or benevolence with condescension.

The African must advance by methods of his own.

A key tenet of his cultural nationalism. He insisted that progress in Africa should not be a mere

imitation of Europe but must be organic, growing out of indigenous institutions and the African genius.

The determining influence which governs a man's action is not the truth as it is, but the truth as he sees it.

This reflects his understanding of perception and motivation, suggesting that people act based on their own understood reality.

The highest service to God is service to man.

A simple, powerful statement reflecting his belief that faith must be manifested

in practical action and dedication to the uplift of one's people and humanity.

The present is only the platform upon which we stand; the past is the root, the

foundation of our being; the future is before us, with all its possibilities.

This quote emphasizes his view of history as a living force, essential for understanding identity and building the future.

The strength of a chain is its weakest link; the strength of a race is the average of its masses.

A call for collective, broad-based improvement, arguing that the true measure of a people is not its elite few but the overall condition of its population.

The time will come when the African will be the teacher of the world in matters of the spirit.

Another variation on his theme of Africa's spiritual destiny, predicting a future

where African values would provide crucial guidance to a materialistic world.

There is no such thing as standing still in life. The law is either forward or backward;

if there is no conscious movement forward, there is an unconscious movement backward.

A Voice from Bleeding Africa on Behalf of Her Exiled Children.

Expressing Blyden's

belief that progress is not optional: either a society moves forward intentionally, or it slides backwards.

We must not lose sight of our African personality.

Perhaps his most famous and enduring phrase. It is the cornerstone of his philosophy of African nationalism

and cultural identity, urging people of African descent to embrace and cultivate their unique heritage.

You cannot know what is right and proper for you by looking at others. You must look into your

own soul, study your own surroundings, and become acquainted with your own circumstances.

A powerful admonition against cultural dependency. He urged Africans to find

their own standards of progress and morality based on their own context and needs.